Fibonacci and Recursive Function Calls

In reply to this question about this exercise. Diagrams made with Lucidchart.

The Beanstalk

The growing beanstalk is an example of the Fibonacci sequence, which is defined recursively …

… simply because there's no other way of defining it. A Fibonacci number is the sum of its predecessor and its predecessor's predecessor, so you absolutely need to know the 8th and 9th Fibonacci number if you want to calculate the 10th.

Now in order to explain how the Fibonacci Beanstalk function works in the computer, allow me to go back quite a few steps and start with some really minimalistic, basics functions, then move on to more complex ones.

The visualizations below try to illustrate what happens when a function is called with a particular input. Here's how to interpret the diagrams:

- a rectangle is a function or operator (functions are light yellow)

- a rectangle with two rounded sides is a value

- an arrow pointing from a value to a function means that the function is called with that value as an argument. Input values to functions are light red.

- a single arrow pointing away from a function and to a (light green) value means that this function returns that value.

- functions have zero or one output. If you see two arrows pointing away from a function, this is not the function's return value, but a schematic representation of what happens internally when the function runs

- every function discussed below has one input value. Binary operators such as

+have two input values and one output, of course.

I think this will all be intuitive enough, so just dive into it.

The simplest functions

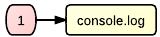

You are probably familiar with JavaScript's console.log. It has an optional input value. It prints that value, but doesn't return anything. So we'll represent it as

Trivial, easy, and boring... Let's move on quickly. Next comes the perhaps simplest possible function that returns a value:

function ident(x) { return x }

The diagram above reads as follows: when you call ident(1), you get 1. In other words, if the (light red) input to the ident function is 1, the return value (light green) is 1 as well.

You can easily see that this function isn't particularly useful or exciting. It just returns whatever you give it. But you already know that 1 is 1, you don't need a function to tell you that. At this point it simply serves to explain my diagram notation.

So how about a function that really accomplishes something? Here it goes:

The black box and its dark innards

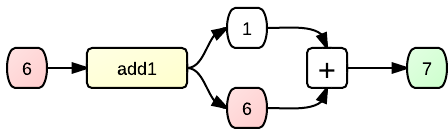

function add1(x) { return x + 1 }

Oh yeah, now we're talking! This little fella here will get you the successor of the number you give it. Number comes in, number plus one comes out. Huge time-saver :) But actually the diagram above is simplifying things a little. It treats the function like a “black box”: you throw a 7 in, and an 8 comes out the other end. If you repeat this enough times with different values, you will quickly get a fairly good idea about what the box does, but you don't actually see how it actually works.

No reason not to have a look inside – let's crack it open and examine it, shall we?

Now we see the inner workings of the immensely useful add1 method. It takes your input value, then magically conjures a 1 out of thin air (amazing!!), then passes both values into an adder (or, addition operator), and this adder takes the two values and produces the (green) result, which the function can then return.

Before we move on, let me elaborate a little on this “black box” metaphor. It can actually be helpful to conceive of a function as a black box, a machine that does one specific job only, does it quickly, reliably and predictably. For the minimalistic example above we know exactly what's happening inside of the machine, because we actually built it. However, most of the time it doesn't really matter to us how a function (or machine) works, as long as we know what it does. For instance, the add1 thing above could actually perform some crazy calculations internally (such as x+(100*100)-9999), and we wouldn't care the slightest bit, so long as it comes up with the answer it was built for. But then again – even if we don't know (or can't know) every detail of how something works, it's really important to understand the workings of your function (or machine) on some level of detail, in order to be able to use it correctly.

For example, I'm sure you're familiar with an inkjet printer. You don't know the exact details of how the mechanical and electronic components inside it work (in fact, no single person on Earth knows all that), but you know that it somehow puts tiny dots of ink on paper, and you wouldn't think of stuffing a hamburger in it, expecting printed pages to come out. You just know enough details to be aware of the fact that a printer cannot process hamburgers, just as the function add1 above can't process paper (it only knows how to deal with __).

And it's not just about knowing what a function cannot deal with at all, you also need to know that a function can behave in different ways depending on what you give it as an input. At this point, we'll cite the fib function, which takes a number n and recursively calculates the n-th Fibonacci number.

function fib(n) {

if (n < 3) { return 1 }

else { return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2) }

}

As you have seen in the very first graphic of this article, the first two Fibonacci are 1, so fib(1) and fib(2) will both return 1, while giving a larger number as input to fib will make fib do something else (hence the else in programming languages). Actually this function is not entirely correct, because it will return 1 for negative numbers (but there's no such thing as a minus seventh Fibonacci number). But we will ignore this, assuming that whoever uses the function knows that they're not supposed to put hamburgers in a printer (or numbers below 1 into fib).

Now the really interesting part, of course, happens inside the else block. We'll look at that in a second, for now just keep in mind that this is exactly the level of detail we must be aware of when we use this function: we need to know that it accepts , that it returns 1 if the input is any number below 3, and that it does something else entirely for larger numbers.

Functions that call other functions

Sometimes one function just isn't enough. There's division of labour, there's the separation of concerns. And in their noble quest to calculate the one result that you so greatly desire, some functions will call other functions, thus delegating part of the job to them and blindly trusting them to do it well.

The example below is a function that will calculate the product of the square of the input and the successor of the input. And it uses two other functions: one that calculates the successor (our friend add1 from the previous section) and one that can square : when you give a 4 to it, be sure that a 16 comes out the other end almost instantly.

We will only take a look at the guts of the outer function, leaving the two inner helper functions alone (as black boxes), because we know well enough what they do and we don't care how they do it. So here's what happens if you feed our new function with the input value 2. It makes two copies of your input. It feeds one copy to each of its two tireless servants, who calculate add1(2) (which is 3) and (2*2) (which is 4), respectively. It then takes the results that the internally called functions return, feeds them into the multiplier, and obviously returns 12:

function add1_times_square(x) {

return add1(x) * square(x) // add1, times, square -- get it?

}

Functions that call themselves (really?)

Now if a function can call another function, it can also call itself (after all, it is a function itself, right)? Functions that (mis)behave in this fashion are known as recursive. You probably learned in your first lesson about recursion that it's crazy dangerous, because just one wrong step can take you into an infinite loop, where you'll be stuck forever, right until the end of the world (or until your browser window crashes, depending on which event occurs first).

So you have been taught to never, ever write code like this:

// I'm an infinite loop! At least I wanna be...

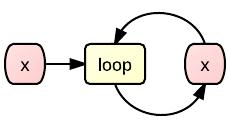

function loop(x) { return loop(x) }

because this function will presumably just take your poor x and feed it right back into itself, right? Like this?

Well, yeah, kinda almost like this. In mathematical theory, for sure, that's precisely what happens. But computers don't work that way. A function never calls itself. Instead, what it does is that it creates a clone of itself and then calls that clone. Very creepy! Actually you can even see this reflected in the code we're written above: loop(x) { return loop(x) } – you see the word loop two times, and the second time is the clone that is created, erm, well, how often actually?

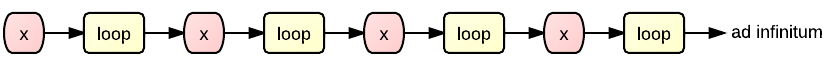

This is what really happens inside your computer when you create an unlimitedly self-calling function such as the one above:

You can read it like this: our program calls the function loop with the argument x,

which calls loop with x, which calls loop with x, which calls loop with x... and so on.

So the function keeps creating copies of itself, and it would do it until the end of time, but your computer has a limited memory, and it needs to keep track of all those hundreds of thousands of copies of both loop and x created every second. Several Gigabytes of memory would in theory get filled to the brim in no time. But most programming languages have a clever precaution against this. They impose a size limit on the so-called call stack (that is the big pile of function instances that are currently open, together with their local variables). Once this limit is reached, you're presented with a nasty error message. (Which is still much better than allowing some broken loop to fill your memory with nonsense and crash your entire machine!).

So the lesson to take home from this is: always try and avoid infinite loops. But not because they're never going to stop – on the contrary, avoid them precisely because they will stop, and very quickly. Like a car stops when it hits a concrete wall. They don't call it crashing for no reason.

But everything I've said up to this point is simply a lengthy introduction which mainly serves to make sure you understand how to read these diagrams. It was a mere foreword to what I actually wanted to explain, and that's how a recursive function works. In case you're still with me: this is where it gets interesting. So let's revisit fib, a simple function that calculates Fibonacci through recursion, and watch it closely as it goes about its business.

The recursive Fibonacci function

You have already seen this code above. Basically the level of detail that we need to understand how this function works is exposed right here in the code:

function fib(x) {

if (x <= 2) {

return 1; // Base case

}

return fib(x-1) + fib(x-2); // Recursive case

}

You can see that the function body only has a simple if construct, with a return for the case that the condition is true and another return in case the condition isn't true. This means that it can only do one of these two things:

if the number 2 or less, return 1

otherwise, call two copies (clones) of

fib: one with the number reduced by 1 and another with the number reduced by 2. Wait for those copies to return results, then add the results together and return that.

In this diagram, you can perfectly see the information flow caused by a call to fib(4). You can also see that, while it only takes one instance of fib to calculate the first or the second Fibonacci number, you already need three instances to calculate the third one, five to calculate the fourth one, and nine fibs just to find out that the fifth fibonacci number is 5:

There are two things we can learn from looking at this monstrosity:

the number of functions that are called internally is almost doubled each time we increase the argument (when we're interested in the next Fibonacci number). This is because every call to

fibwith an argument larger than2will cause two additional calls – each of which may in turn cause two additional calls, and so on. This is why the Codecademy exercise author warns you not to go over 40 with this recursive Fibonacci calculation function. Creating all those extra clones offibis a very memory-consuming process.the algorithm is terribly inefficient. You can easily see that

fib(3)andfib(1)are calculated twice, andfib(2)is even called three times in the process of calculatingfib(5), and this waste of computer resources gets worse with larger .

So to conclude, it's actually not a good idea to write a Fibonacci number generator using recursion.

I hope you found this little educational text useful or at least entertaining. It is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike. Feel free to copy, modify, or sell it, just be sure to include a reference to this page as the original source.